7 November 1928 – 4 June 2025

Professor Raymond Henry Charles Warren, who has died aged 96, was part of that Interwar generation of British composers that owed a stylistic debt to Tippett and Britten (both of whom taught him). Along with his contemporaries Kenneth Leighton, Alun Hoddinott, John Joubert, and William Mathias he divided his time between composition and University teaching.

Like them he was a composer who taught, rather than a teacher who composed but also someone who took teaching seriously, so leaving a twin legacy of inspiring compositions and inspired students, many of whom continue to work at the heart of British musical life.

Born in Weston-super-Mare, he was the eldest child of Arthur, a Maths teacher and keen amateur musician, and Gwendoline Warren (nee Hallett). He attended Bancroft’s School and among his peers were several boys who went on to become talented professional musicians including the flautist Fred Lowe (the LPO and Covent Garden), the actor Denis Quilley (who premiered the title roles in the first West End productions of both Bernstein’s Candide and Sondheim’s Sweeney Todd) and Niso Ticciati, the grandfather of the conductor Robin Ticciati, as well as the poet John O. Reed.

Despite the thriving extra-curricular musical life at Bancroft’s there was no music teacher. Despite a consultation lesson with Britten (and glimpsing the handwritten score of Peter Grimes, then a work in progress) that had convinced Warren he wanted to be a composer, he couldn’t take A Level music and so went up to Cambridge initially to study Maths, transferring to music, under Robin Orr, from his second year.

From 1955 he taught at Queen’s University Belfast, where he was the first person in the UK to be given a personal chair in composition in 1966, before becoming Hamilton Harty Professor of Music in 1969. Though now receiving national attention The Pity of Love was written for Pears and Bream to perform at the 1966 Aldeburgh Festival) Warren himself remained convinced that a composer should primarily be useful to his own community.

He became Resident Composer to the Ulster Orchestra and a key figure in the wider musical scene. As the atmosphere in Northern Ireland grew increasingly tense his music became a witness to events. Songs of Unity (1968), a work written for children and celebrating ecumenism, was picketed by Ian Paisley at its premiere. The violence of The Troubles informed his powerful Second Symphony (1969) reflecting both the conflict and the grief that united Catholics and Protestants alike.

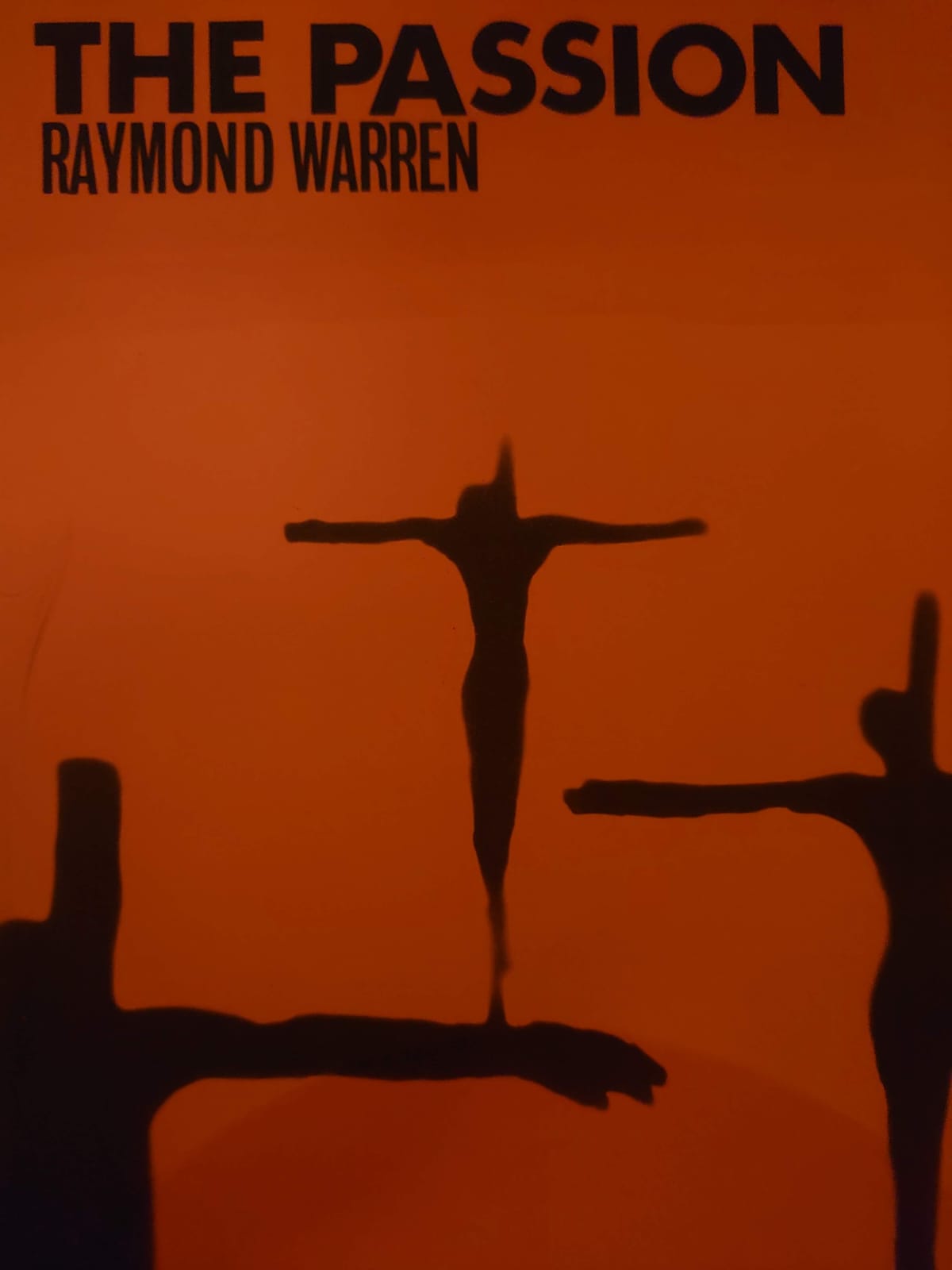

The brother of two notable priests, Alan and Norman Warren, many of his pieces were concerned with Christian responses to suffering. From Drop, Drop Slow Tears (1960) and The Passion (1962) to Salvator Mundi (1976) Warren’s compassion and empathy are evident, but the horror of the Troubles in Northern Ireland infuses the second Symphony with a desperate urgency that make it required listening.

From the startling violence of its opening to a final movement that’s a searing lament for the suffering of a whole society; it is perhaps the purest musical expression of the Northern Ireland conflict. In this music conciseness of thought and expression leads to clarity and a disconcerting honesty; there’s no false comfort. In Warren’s music, consolation and beauty are earned consequences of the musical discourse.

In contrast to the growing sectarian violence Queen’s University, Belfast and the wider community around it had provided the young composer with both inspiration and opportunity. The Belfast Festival at Queen’s (now the Belfast International Arts Festival) has started in 1962 and bringing artists who were, or were about to become, internationally renowned to the province as well as celebrating local talent and providing a platform for his music.

During the 1960s the Belfast Warren wrote music for numerous plays at the Lyric Theatre, Belfast, including the complete plays of W.B. Yeats. Other notable collaborations followed, in 1970 with the choreographer Helen Lewis There Is a Time and with fellow lecturer Seamus Heaney A Lough Neagh Sequence. Heaney made a recording of his poetry with Warren’s music in 2011, shortly before his death.

He left Belfast in 1972 to take up the chair in Music at the University of Bristol, retiring from teaching in 1994 but remaining active as a composer and mentor until recently. His post-retirement works spanned from the exuberant Symphony No.3 Pictures with Angels (1995) to the Cello Requiem (2018) and included a string of beautifully crafted works commissioned for performance by children, teenagers and amateurs. These include two chamber orchestra works Ring of Light (for Marimba, Organ and Strings) and A Star Danced for Solo Cello (his instrument) and Orchestra, the Variations on a Gloucester Chime for the Bristol School’s Philharmonic, and in 2014 the Gwent Carnival Overture for the Abergavenny Symphony Orchestra.

Pieces written with young people in mind were a constant thread in his career from the children’s opera Finn and the Black Hag (1959) to his charming score for Ballet Shoes written for the London Children’s Ballet in 2001 and revived by them in 2010 and 2019. He wrote two operas for school children for performance in Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral in the 1970s and another, In the Beginning, premiered in Clifton Cathedral in Bristol in 1982.

He also wrote pieces about childhood and his delight in play is evoked most strongly in his set of four choral miniatures based on Children’s singing games Golden Rings (1987). This distinctive aspect of his musical style was later used to communicate something altogether more psychologically complex in the song Children’s Games from his wonderful orchestral song cycle of poems by Louis MacNeice: In My Childhood (1998).

Warren’s love of games, perhaps influenced by his mathematical background, ran deeper than that. There is an underlying playfulness in his manipulation of musical material which was derived from the approach of Bartok (with occasional serialist thinking). He was very proud that Britten had praised the rather Bartokian inverted canon at the opening of his opera The Lady of Ephesus (1959).

Clear sighted that he was not the sort of composer that creates new techniques, but rather that creatively uses techniques in new contexts, another key influence was Tippett with whom he studied privately from 1952-1960s. He absorbed something of Tippett’s rhythmic energy, in fact, his music was infused with a Tippettian vitality, even when stylistically it departed from the model of his mentor. In these passages we often find a good humour that came from his own personality and a forward momentum that seems related to his love of the telling of the anecdote, a natural tendency perhaps reinforced by his years in Northern Ireland.

If one work best represents all his varied concerns, it is perhaps his 1989 oratorio Continuing Cities written for the centenary of Bristol Choral Society. Taking as its text poetry inspired by the cities of London, Chicago, Hiroshima and Jerusalem, the four-movement structure allowing a symphonic level of thinking. A continuous 55-minute span, each movement is framed by words from George Herbert’s Antiphon with three soloists (S, A, Bar) presenting the human view and the choir that of the angels. Here play, vitality, suffering and joy are presented in music that as vivid, luminous and singable as any large-scale choral work written in the last quarter of the 20th century.

Warren’s much-loved wife Roberta predeceased him in 2022. He is survived by his four children Tim, Christopher, Ben and Clare and eight grandchildren.

Written by Edward Davies

- To enquire about Raymond Warren’s music please email edwardddavies@hotmail.co.uk