A transcript of Matthew Taylor’s talk from the BMS AGM 2021.

As a young composer in the early 80’s there was the sense that the erstwhile leaders of the old European avant garde were still establishment, just, though their supremacy was becoming increasingly questioned or even threatened.

To my ears then, the composers of these tendencies who were writing music which we were meant to find ‘challenging, innovative, ground breaking, stimulating’ translated to being over-complex, self – defeating, impenetrable, pretentious and usually without any connection or identification with the things in music that were cherished.

And whilst the emergence of minimalism around that time provided a welcome relief for many from the complexities of the avant-garderie, its ethos seemed desperately limiting and limited in artistic expression.

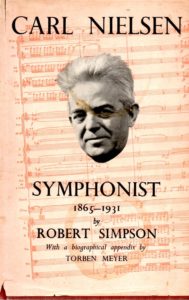

I knew Robert Simpson’s name before encountering his music, first as the author of the still definitive biography of Nielsen, who was and still remains one of my Gods, and later as one of the most compelling speakers on Radio 3 whose penetrating talks on Beethoven, Haydn or Bruckner are still amongst the finest of their kind. My instinct was that his music would be good also and there would be plenty to gain from it. I was right.

His output is not vast; central to it is the cycle of 11 symphonies and 15 string quartets. I feel very proud to be the dedicatee of his last symphony.

In the early 1980’s there were many that branded Simpson as a conservative, but there was very little about the man or the music that suggested that, and politically he was a fierce opponent of any form of conservatism.

Paradoxically, one of the most pertinent appraisals of his music came from an American writer who summed up his output thus, ‘ … a lifetime’s inspiration through which one determined Englishman hurled down the gauntlet of the self regarding second half of the twentieth century and helped justify once more music’s claim to be the most elevating, questing and stimulating accompaniment to the life we all lead.’

Bob Simpson’s music remained cussedly unfashionable throughout most of his lifetime. He was unconvinced by Schoenberg and said so, thereby alienating himself from many areas of the post war British Musical Establishment. He was derisive of the gimmickry of the 60’s and 70’s avant garde, and if he’d lived into this century, would no doubt have been as trenchant a critic of both the soft centred, diluted ‘easy listening’ muzak as well as the decorative, intricate textural doodlings which do what they do merely to conceal an absence of real substance.

Neither was there a sense that Bob’s music represented a continuation of the essentially English Pastoral idiom though he responded very warmly to much of Vaughan Williams, early Tippett and other composers of similar outlooks.

Bob’s ideal was to recreate something of the energy, momentum and life force of Beethoven, never to copy him, but to bring the spirit and essentials of the German composer closer to modern consciousness. Allied to that he showed a great spiritual kinship to Sibelius and Nielsen. As Bob was a powerful creative artist his language was cultivated through his enthusiasms which acted as important influences whose fusion produced one of the strongest voices in late 20th century music and one that is still undervalued, under appreciated or simply ignored whilst others of infinitely lesser stature are given the red carpet treatment.

The first Simpson I heard was the premiere of the 6th Symphony. It knocked me flat, and shortly after that I bought the recording of No.3 which I found equally impressive, for here was music that showed an allegiance to the great heritage which I knew and loved but built upon it to create something cogent, strong, vital even at times uncompromising.

At 18 I wrote to Bob asking for lessons. He replied saying that he didn’t offer tuition being too hesitant to propound his views to others but he invited to me to lunch instead.

So we first met in January 1984; the knowledge and wisdom that he imparted, ironically, far exceeded what might have been gained from conventional lessons. We became firm friends quickly and when he moved to County Kerry in Ireland in 1986 with his wife Angela, I used to visit them regularly for weeks in the Summer.

They were magical times, talking at leisure, walks on the beach, looking far West over the view of the Atlantic ocean and listening to Bach, Beethoven, Bruckner, Reger, Simpson and many others. I was in the company of an alpha plus musician.

In 1991, Bob suffered a debilitating stroke which resulted in severe paralysis of his left side and continuous pain. Though further composition became almost impossible he remained mentally alert with a seemingly limitless profusion of jokes, few of which were clean.

He never said ‘Why me?’ feeling that that really meant ‘Why not somebody else’ as he wouldn’t wish his condition on anyone. He was defiant, selfless and altruistic right to the end, ‘I’m no shallow optimist but I’m a ferocious anti – pessimist’ he once said. This was certainly manifest in the man and the music.

Matthew Taylor